Dungscape

Connecting art, natural science, and conservation to showcase the ecological importance of healthy dung.

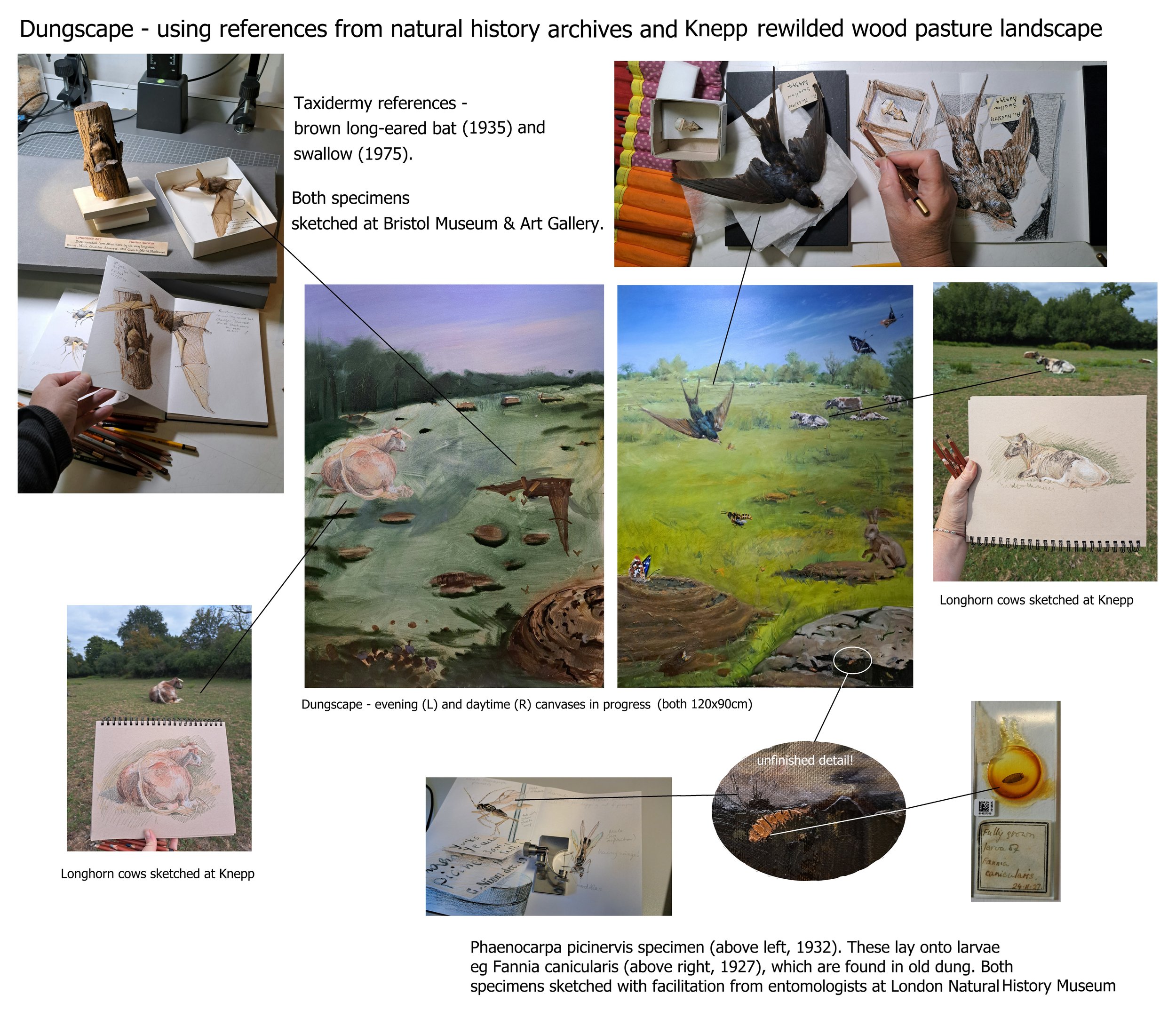

“Dungscape” draws on museum natural history collections and rewilding projects to inform a series of (in progress) oil paintings. These landscapes demonstrate the wildlife community that thrives around dungpats in the absence of chemical pesticides and fertilizers.

This project is generously supported by The Society of Wildlife Artists’ Natural Eye bursary award.

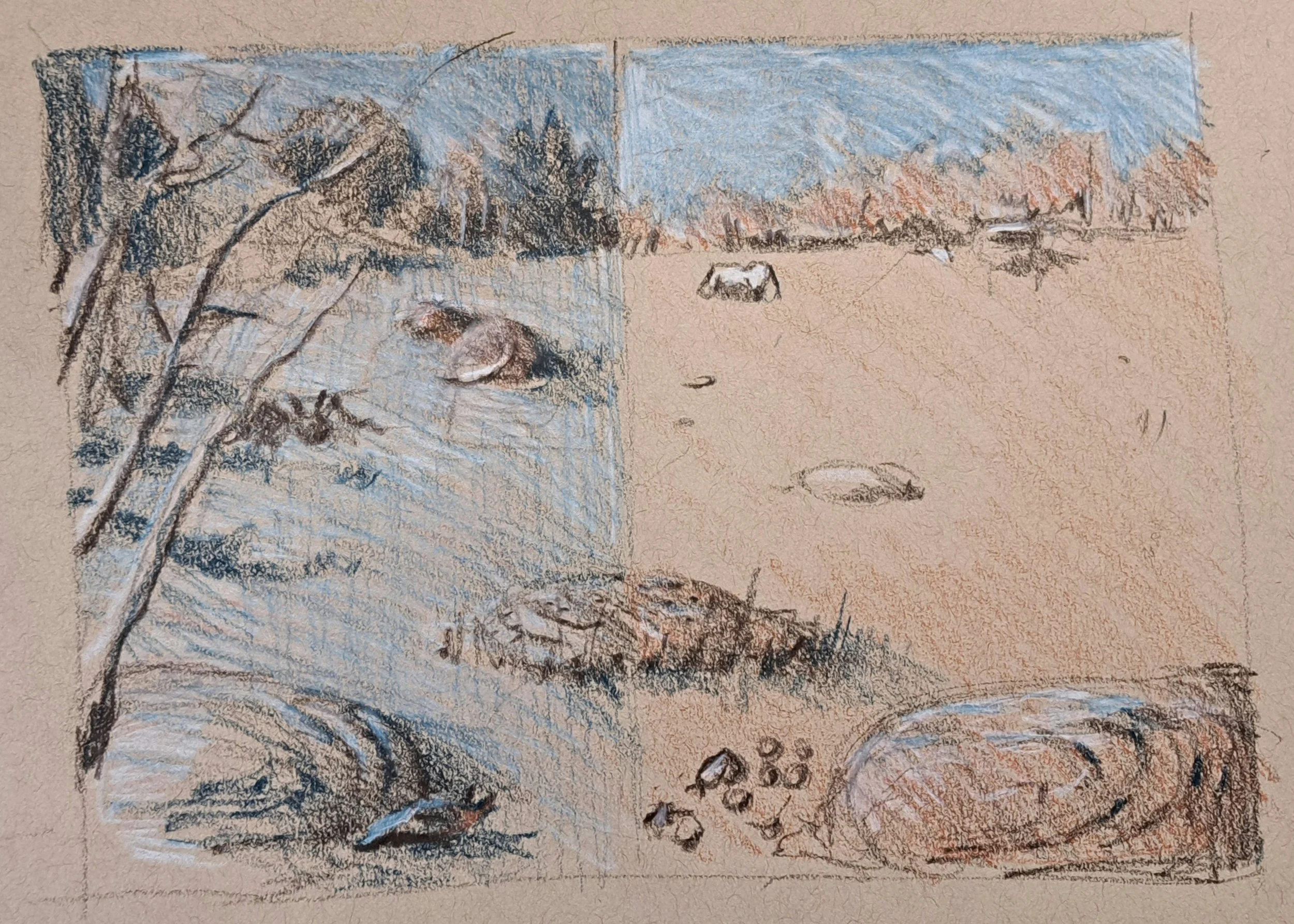

Sketchbook

A set of preparatory studies in a concertina sketchbook, mostly from museum collections, many using a microscope, completed between July and October 2025. The specimens match this spreadsheet of candidates for Dungscape oil paintings.

The spreadsheet holds information from my observation, research, and conversations with curators (see acknowledgments and references). This is designed to ensure the finished paintings are credible in terms of behaviour, scale, context etc.

The sketches highlight museum collections and curators as a direct source of artistic reference. My favourite figurative art is both expressive AND anatomically correct. In the context of such an ecosystem, the creatures have behaviours and characteristics that as a layperson I would miss. For example that only male purple emperor butterflies have iridescent wings and visit dung, or that ‘late successional’ fly larvae wouldn’t be present on a steaming fresh dungpat. By including labels, pins, and notes, the sketches draw attention to the cumulative inheritance of collections, and the value of organisation, preservation, and documentation.

Series of 3 oil paintings (in progress)

The Dungscape paintings are pastoral scenes, with flowers, trees, and cows based on the native Longhorn cattle at Knepp estate. Bats and swallows swoop overhead catching insects on the wing.

With dung (cow and rabbit) in the foreground, pronounced foreshortening allows the smaller invertebrates (such as parasitoid wasps) to be scaled up to be easily visible.

To enable realistic settings for nocturnal and diurnal wildlife, the first two paintings will form a diptych, one set in daylight, the other at dusk, to read as a continuous plein air landscape when hung adjacent

The third painting will show both day and dusk on the same landscape. On Gator Board/similar, robustly varnished to enable visitors to touch it, such that it could be included as part of a museum display, keyed to reference items in the collection. The foreground dungpats will be painted as though intersected by the front of a glass case, so that the interior wildlife (eg dwelling and tunnelling beetles) can be illustrated.

Joining the dots

I hope that Dungscape can highlight and foster connection between the passionate pockets of people working towards connected goals of biodiversity and nature recovery.

Entomologists, from hobbyists to eminent science professionals, have for centuries collected specimens, sorting and preserving them as a cumulative resource held in historic collections such as Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, and The Natural History Museum. Locked within these (and larger creature) irreplaceable specimens are insights about species evolution, immigration, habitats, anatomy, and more. Scientists continue to develop understanding from them, as sampling and viewing technologies evolve. The labels, holding information about collection location and date, are often “more valuable than the specimens for what they can tell us”.

As collections are digitised, the possibility of sharing reference material between institutions expands.

Conventions, hobbies, and understanding of best practice are changing, so curators tell me that the numbers of personal collections being bequeathed into museums is slowing down. They are therefore even more keen to make sure what we (they are national collections) have is preserved.

Out in the literal field (or wooded pasture and scrub), rewilding projects such as Knepp have demonstrated spectacular improvements in biodiversity. Free of artificial pesticides and fertilisers, trampled, grazed, rootled and fertilised by old breed cattle and pigs, their sites are a magnet not just for flora and fauna, but for natural scientists keen to study the same. Enter the entomologists, in stompy boots with sieves, jars, and sticks… meddling in and under dungpats, revealing the hidden, finely balanced ecosystems with extraordinary stars. Dung beetles are a keystone species in this system.

But when these ecosystems are interrupted (eg with anti-parasitic drugs used to treat domestic pets and intensively farmed cattle, that persist in their dung and wipe out the dung beetles), they collapse. Quietly.

Through Dungscape I hope to demonstrate the interconnected and fascinating ecosystem that exists around ‘healthy’ dung. But also the interconnected human ecosystem of co-operation and cumulative knowledge that exist between generations of hobbyists, curators, scientists, farmers and ecologists:

Related work

I have made a suite of short videos (<3mins) recording my museum visits and sketches, featuring the curators who have helped. Some of these are already available here:

If you know of an institution that might be interested in sponsoring/purchasing/exhibiting this project, please don’t hesitate to get in touch. I have committed to two exhibitions (September and October, more news to follow), and am seeking to write one/more articles for publication. Other related work (examples below) are ready to exhibit alongside. I would be open to licensing/merchandise using the copyrighted images.

3D high resolution image of a 98 year old fly larva, anyone?!

Artist Statement

Hello from Bristol, UK, where I try to make sense of things by painting and drawing. Click here for more about me and my art practice.

I hope that Dungscape brings you a moment to stop and marvel at the ecosystem that functions around a healthy dungpat. Free from the chemical pesticides (eg avermectins) and inorganic fertilisers that are characteristic of contemporary intensive farming practice, Knepp and other wilded landscapes support native breed cattle, providing fertile ground for keystone species (eg dung beetles), and a rich assortment of interdependent creatures. These have evolved to work together to naturally manage harmful parasites, and to precipitate the absorption of dung back into the soil.

Acknowledgements (in progress)

This project would not have been possible without the help of the entomologists and curators who have given me advice on which species would be on a dungpat, where, and doing what.

They have been extremely generous with time and access to reference material, including the collections in their care (titles at time of writing)

Ray Barnett - Senior Vice President of the British Entomological & Natural History Society

Gavin Broad - Principal Curator in Charge, Insects (specialism hymenoptera) at the Natural History Museum, London; Vice-President (president-elect) of The International Society of Hymenopterists and the British Entomological & Natural History Society

Miranda Lowe - Principal Curator and museum scientist at the Natural History Museum, London

Erica McAlister - Senior Curator for Diptera and Siphonaptera, Natural History Museum

Nick Pope - volunteer natural sciences curator at Bristol Museum and Art Gallery

Rhian Rowson - Natural Sciences Curator at Bristol Museums, Galleries & Archives

I am also very grateful to the following entities for kindly providing invaluable access and help:

References

Digger wasps are incredible creatures. I wanted to find a photo of one carrying a fly, and the best one came with a moving story: This fantastic photo was taken by Kieran Metcalfe, who died in July 2025. The image here links to his website, where I recommend reading his notes on how he captured these fascinating creatures in action. Kieran’s photography can be licensed for use via his website. Proceeds to The Christie Charity.

Images clickable:

Peter Skidmore - “Insects of the British Cow-Dung Community” (click here to access on archive.org)

Isabella Tree - “Wilding” (also available as audiobook narrated by the author)

Erica McAlister - “Metamorphosis - How insects are changing our world”

Draw Wing - website on insect identification by wing details